Blog 7

24th – 27th March

Sol de Manana – Volcan Licancabur – Quetena Chico and Volcan Uturuncu

Total distance – 1307km

The southwest corner of Bolivia is an unworldly place. Just before reaching Laguna Colorada, I entered the Eduardo Avaroa Andean Fauna National Reserve, home to a treasure trove of natural wonders. The reserve’s major attractions are erupting volcanoes, hot springs, geysers, lakes, fumaroles, mountains and its three endemic species of flamingos in particular.

In researching the topic of what the mountains mean to the Andean people, past and present, I found out that the mountains have always been venerated by the Andean people, considered the main sources of water, fertility and livestock. As such, the mountain peaks make up the axes that give meaning to the landscape. Two of the primary mountains for the Andes cultures are Licancabur and Uturuncu.

I originally planned to cycle down as far as Volcan Licancabur and then on into Chile, but that plan was thwarted by the Chile border closures. Visiting Licancabur is still important to the story I want to create, so we took a diversion, driving from Laguna Colorada, to Sol de Mañana, Polques and Licancabur (before resuming the cycle journey from where I stopped pedalling at Laguna Colorada the next day.

We drove to almost 4950m elevation to see the first attraction on our diversion, the giant volcanic cauldron – Sol de Mañana. Here some of the Earth’s energy comes bubbling and hissing to the surface. Sulphurous steam pours constantly into the atmosphere and gloopy mud boils in the pools.

Sol de Mañana was used as a testing ground for NASA’s Mars Rover and it is easy top see why. It is the one place on Earth that has similar conditions to Mars at altitude it is cold, bleak but void of snow and glaciers.

The Bolivian government is in the process of harnessing the geothermal energy from Sol de Mañana to sell, most likely to Chile. Nearby there was a lot of development and activity such as laying the pipes.

Moving on towards the far southwest corner of the country, we stopped at Polques, famous for its mineral springs, before heading for Licancabur.

Volcan Licancabur

Towering above the aquamarine waters of Laguna Verde in the far southwest corner of the Bolivian Altiplano is Volcan Licancabur. Located on the Bolivia/Chile border, the crater lake on the summit of Licancabur is said to be the world’s highest lake.

Licancabur is one of the most sacred of all mountains in the region. The mountain was particularly attractive to the Incas because of its almost-perfect symmetrical cone shape, and its height – 5921m.

The Incas used the sacred mountain to perform sacrifices and ruins can still be found near the summit. Mountain worship and sacrifice was a common feature across all Andean cultures over the centuries, but the high mountain sites, those that are 5200m and above, have all been attributed to the Incas. It seems that only the Incas had the knowhow, organisational skills and motivation to go higher than other cultures, whether it be a show of power to dominate the cultures they conquered or to impress the Gods to secure their water sources, fertility and ultimately, their prosperity.

High on the saddle between Licancabur and its neighbour, Jurisques, at just over 4600m, lies the ruins of an Incan tambo – used as a base camp to prepare for the ceremonies on the summit, and to acclimatise. The site first belonged to the indigenous people of the region – the Kumsa. The Kumsa lived there long before the Incas came through and displaced them so they could use the site for their purposes.

Toby and I scrambled up a rocky climb to the tambo to explore the site. I had a sketch map of the ruins but without a guide, it was hard to know exactly what we were looking at. There was so much to see. I tried to imagine what might have taken place in the main rectangular courtyard – religious gatherings, sacrifices, preparations to scale Licancabur.

The 360 degree views were amazing, with Licancabur towering above and Juriques, often referred to as the ‘bleeding mountain’ because of its red iron-based rocks on the east side. Sairecabur, which is just to the north of Licancabur, would have been a 7000m mountain before it blew its top. At the base of Licancabur is Laguna Verde, which gets its green colour from the copper content in the water – according to Rolando, it is not as green as it once was.

We travelled back to Polques to stop for the night and in the morning drove back to the point where I stopped cycling at Laguna Colorada. The aim of Day 25 was to reach Quetena Chico, only 53km away. Rolando said there was a climb, but from the lake level, it looked fairly innocuous. However, I always seemed to be chasing the horizon, climbing a steady 3-5% gradient on varying surfaces. Nearing the summit, the road became a rollercoaster, each peak higher than the previous one. The dips were filled with monster corrugations ensuring I couldn’t get any momentum to climb the next slope.

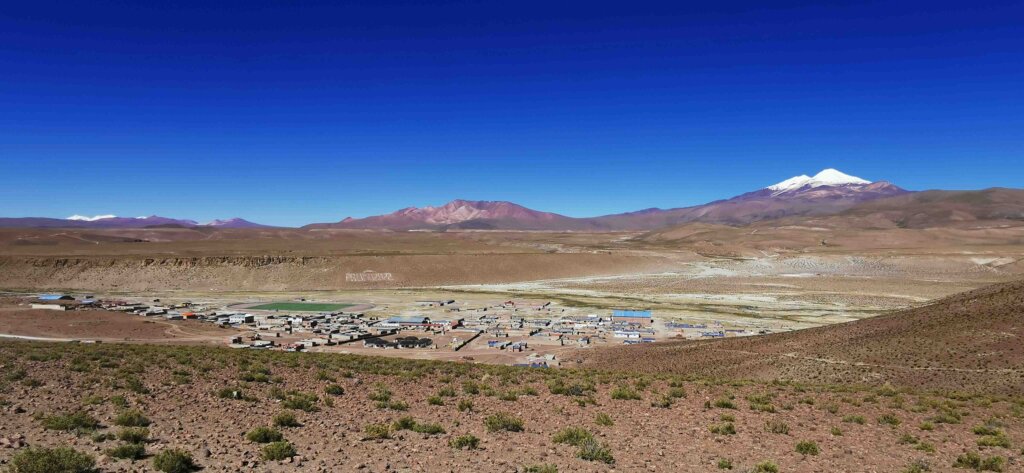

After about 25km I finally reached the summit – 4850m – where I caught the first glimpses of Volcan Uturuncu, the 6008m volcano I was planning to cycle up (as far as the track goes). The descent to Quetena Chico (4145m), the village at the base of Uturuncu, was a lot of fun, except the road was incredibly rough, mostly very stoney. Always Uturuncu was looming in front of me. It was a majestic sight but knowing I was going to climb it made me feel humble and very insignificant. Rolando said, “think of David and Goliath”.

Quetena Chico has a bit of a Wild West feel about it with its dusty streets set in a valley flanked by rocky gorges and cliffs. Our accommodation is clean and well-managed, a perfect base for climbing Uturuncu.

Volcan Uturuncu

As with many volcanoes in the region, Uturuncu has been mined for sulphur. The abandoned Susana mine is about 9km from the town and there is another ruin near the summit, which is the reason why the track was built up the mountain. The mines however have been disused for many years and no maintenance has been done on the track except for clearing major rockfalls that block the path. The track is extremely rough, mostly stoney, and where there are few stones, there is sand. The gradients are notoriously steep. The track, that goes as far as the saddle between the twin peaks, reaches an elevation of 5770m and has for several years been recognised as the highest cycleable track in the world. I wanted to give it a go over two days. It is 30km from Quetena Chico to the summit.

The aim of Day 1 was to reach at least half of the altitude. Out of Quetena Chico (4145m), I crossed a small stream and followed the rough track through spectacular valley for 2.5km before the climbs started – sharply. Very quickly I was looking down on the valley and gorges, coping with one stoney/sandy climb after another. Most gradients were around 10% according to my Wahoo cycle computer.

After 8.3km I came across the first derelict sulphur mine, the sulphurous odour and the yellow ground was a bit of a giveaway.

After a brief levelling off, the stoney track rose sharply ascending an open plain, so steeply at the end I had top push the bike (for the 14% gradient). At that point, 15km done, we stopped for a lunch break. From there it was into a series of hairpins, 8-12% gradients where a lot of energy was also going into staying on the bike and avoiding the huge stones, wash aways and loose gravel. I managed 5km without stopping, reaching an altitude of 4939m over 20km. That was enough for Day 1. I was really pleased top be able to hang in there to reach that level.

On Day 2 we left early, taking an hour and a half to drive to where I stopped the previous day. This time, as required, we had to bring a guide with us, Marcos. It is pretty tough starting on a 10% gradient at around 5000m, but I felt empty – there was nothing in the tank. I think a big part was the altitude (although I have cycled to 5360m before, the road was much easier), I had really pushed above and beyond the previous day and this was my seventh day since Uyuni without a complete day off the bike. We are also finding it difficult to get enough of the right food and breakfast was woefully inadequate for doing this level of activity.

I cycled for only about 1km of the 7km I did on the second day, the rest I pushed. The average gradient was 10%, the steepest around 16% and it was all rocky or soft. The limit for vehicles was 5550m and just above that the snow started to block the track. Often Uturuncu is clear of snow, but as we have found is consistent with this colder, wetter season, the mountain was carrying an unusual amount of snow. I had to pull the pin at just below 5600m, 3km away from the end of the track (which was under snow). I was a bit disappointed not to get to the end of the track, but still pleased with the effort, that I had pushed that far under my own steam and to see Quetena Chico as a speck in the distance.

Before I sign off, thank you everyone who has been sending me your supportive comments. It inspires me to keep turning the pedals. They mean a lot to me, even though I can’t reply to them very well.

Bare & barren Bolivian landscapes – yet you’ve shown us so much beauty. Thank you, Kate.

A really fascinating adventure!

Dear Kate

Inspiring stories, which I can follow on the map. I am ready to leap aboard and try the Bolivian mountains, maybe taking the land route south from the glorious Colombian Amazonas areas, now a little more opened up.

Thanks for the journey, the geography and always the related historical narrative.

Hi Kate. I have just caught up with all your blogs so am up to date with you trip now. Your days are just one big ‘wow’ after another, for landscape, organisation, physical effort. Hearing about all those corrugations brings back memories of the outback, and the sickness, too, from Siberia. It is all fascinating and the photos are great – they do manage to convey the scale of it all, and the barrenness is stunning. Looking forward to the next instalment.

Greg Y.

Good job Kate. Hope you can get some decent and adequate food soon!