Blog 20

Days: 101-102

Dates: 20th-21st September

Denham

Total Distance (2021 + 2023) : 8617km

Between spending a couple of weeks in Western Australia with family and friends post-expedition and returning to life in Melbourne, it has taken a while to write the final blog – so here it is.

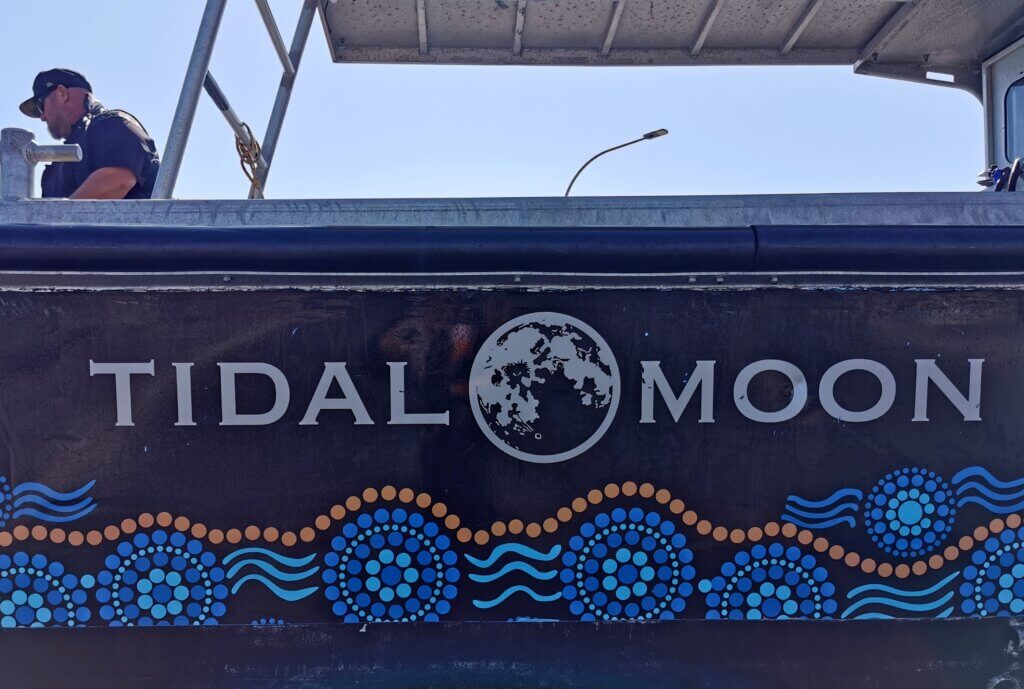

I was introduced to Tidal Moon founder, Michael Wear through marine conservationist and philanthropist, Jock Clough and The University of Western Australia Professor Gary Kendrick before the expedition started, and flagged the opportunity to include the initiative as an important story at the end of my journey.

After finishing the expedition at Steep Point, my wonderful support team dropped Mark and I off in Denham (Australia’s most westerly town) on the Peron Peninsula to meet Sean McNeair, Alex Dodd and Ralph Wear, proud Malgana (saltwater) people from the Tidal Moon team.

The Tidal Moon Sea Cucumbers project is a collaboration with three Aboriginal communities, Malgana (Shark Bay), Bayungu (Coral Bay / Exmouth) and Thalanyji (Onslow), which is developing a viable commercial sea cucumber business, training and supporting the next generation of local First Nations people, while maintaining cultural heritage and environmental stewardship. Out of this aquaculture project a unique and significant blue carbon biodiversity restoration project has also emerged.

The Malgana people have lived in the Shark Bay or Gathaagudu (“Two Waters”) region, for at least 30,000 years. From about 1700 until 1907, hundreds of fishermen sailed each year from Makassar on the island of Sulawesi to the Arnhem Land coast to trade with Aboriginal people for sea cucumber, which is still used for food and medicine. Michael’s vision is to re-establish this historic trade with Southeast Asia with a holistic, long term approach that will keep the Malgana community strong and safeguard the environment for generations to come.

Sean McNeair, aka Moose, the Offshore Operations Manager gave Mark and I a tour of the pristine factory where the sea cucumbers are processed. Essentially the sea cucumbers are cleaned and dehydrated until the product is preserved, concentrated down to a fraction of its original size. Several large bags of the end product were being stored in the facility, ready for export to Singapore, but production was on hold while the complicated fishing licence was renegotiated. Moose told us that positive news had just been received and they are now able to resume the sustainable harvest and export of the valuable commodity.

While Tidal Moon’s focus is sea cucumber fishing, it has also established several exciting partnerships with the likes of the CSIRO, APEC and the Harry Perkins Institute of Medical Research, helping the latter determine the health benefits of sea cucumbers, particularly in cancer treatments. Sea cucumbers have the ability to eject their internal organs and grow new ones. They are loaded with collagen and the pending discoveries of new health benefits will surely boost Tidal Moon’s business and subsequently, benefits to the Malgana people.

Moose echoed what Michael had previously told me, that they want to be in the mainstream industry and have the ability to set up a business that’s not reliant on grants or government funding but stands alone as a successful First Nations-owned company.

Moose and head diver, Alex Dodd, had planned to take us out on their boat the next morning to dive for sea cucumbers but the forecast was for strong winds which would have made our trip out to the Steep Point area too rough. Instead we opted to focus on the environmental stewardship side of their initiative, the protection and restoration of seagrasses in Shark Bay.

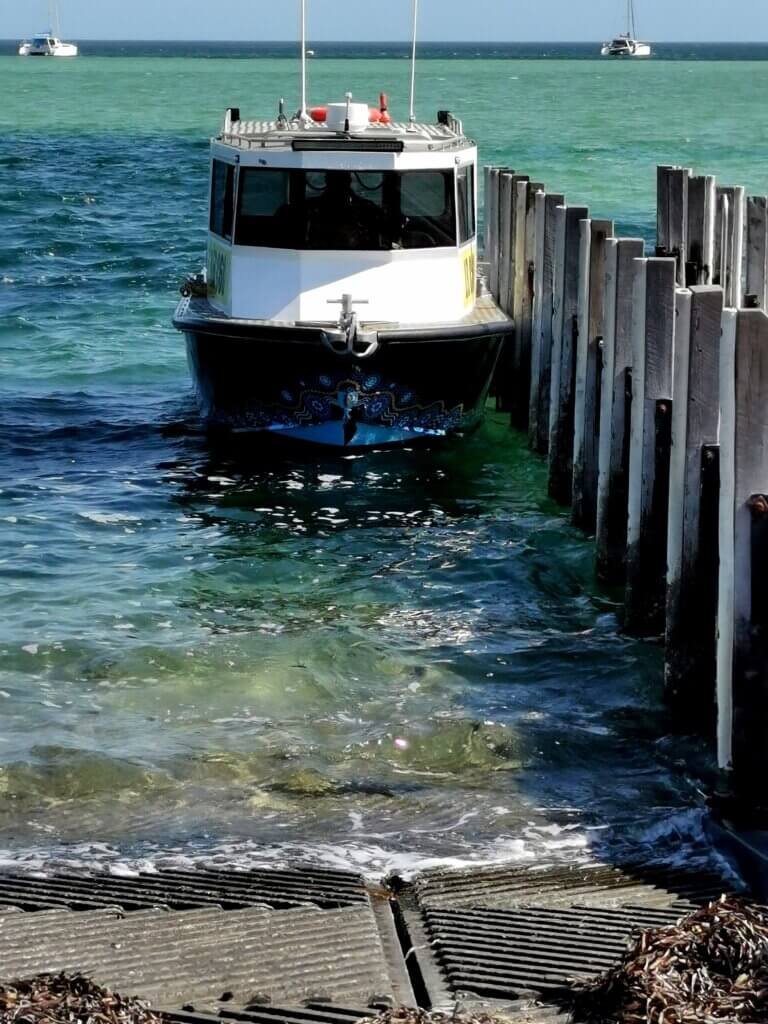

We set off early from a small jetty on the Denham foreshore, tracking north along the Peron Peninsula coastline.

Shark Bay is home to more than 1500 marine species and some of the largest, most diverse seagrass meadows on Earth. Seagrass, or wirriya jalyanu, is not the same as seaweed; seagrass is a flowering plant while seaweeds are algae, which do not produce flowers. The ancestors of seagrasses are land plants that moved back into the sea, and evolved the ability to live in salt water. The Shark Bay seagrass ecosystem covers some 4000 square kilometres of sea country. The sheltered bays, shallow waters and sandy seafloor are perfect conditions for seagrasses to grow. The seagrasses slow water flow and trap sediment, creating crystal clear waters. The two most common types of seagrass in Shark Bay waters are Amphibolis antarctica (wire weed) and Posidonia australis (ribbon weed).

Seagrass ecosystems are important because they form a habitat that supports incredible diversity. They are classed as a blue carbon ecosystem which is up to five times better at storing carbon than rainforests. Seagrasses need a lot of light for photosynthesis which is why they thrive in Shark Bay’s shallow waters. They take carbon dioxide out of the water, use it to grow leaves and rhizomes, and release oxygen into the water for animals to breathe. ‘Blue carbon’ includes buried organic carbon beneath the sea floor. This greenhouse gas filtering process by seagrasses accounts for five percent of all the carbon stored in the world.

In the summer of 2010/2011, a marine heatwave affected the west coast of Australia. The waters in Shark Bay warmed up so much that many seagrass plants lost their leaves and died. Up to seventy percent of the bay’s seagrasses died or were severely impacted. When large amounts of seagrass die, the effects cascade through the food web, with loss of grazers such as turtles and dugongs, omnivores such as crabs, carnivores such as sea snakes, filter feeders such as the Shark Bay scallops and, of course, sea cucumbers. Up to nine million tonnes of carbon is estimated to have been released in this heatwave event.

Tidal Moon has been working with UWA to design the most effective scientific method to restore the seagrass meadows of Shark Bay. This partnership has enabled the Malgana people’s traditional knowledge and skills, focused on managing country, to be integrated with western science, with a view to bringing these meadows back to full health.

The main purpose of our boat trip was to check on some small underwater plots where seagrass seedlings had recently been planted to see whether they had started to grow.

We then travelled a little further along the peninsula to check out the amazing coastline

By midday, the wind had picked up and we headed into some choppy seas on the way back to Denham.

The highlight of the afternoon was a trip to nearby Little Lagoon, a beautiful saline lake connected to the ocean via a tidal creek. Sean’s knowledge of his local land and sea environments, and how to care for them was a stand out for me. He is also mentoring Alex who, according to Sean, is soaking up the knowledge like a sponge. They are always alert to the nature around them; the overall health of the ecosystems, the species, how many, tracking animal movements, noticing small details, the changes from season to season, etc. They are a part of the environment and care for it as if it is an integral part of them.

Tidal Moon has taken six years to develop from a promising concept into a sustainable, holistic business model – revitalising the pre-colonial sea cucumber trade, caring for the environment and providing training and dignified work for the Malgana People of Gathaagudu, with many more possibilities on the horizon. There’s much that others – indigenous and non-indigenous – can learn from this successful model. During our final interview, walking beside Little Lagoon, Sean eloquently summarised the need for more two-way learning to advance cross-cultural understanding and the need to preserve cultural heritage while also learning to prosper in contemporary society. His sentiments echoed the future hopes of the Elders and leaders of all four communities that I featured on my journey across the country; the Wangkanguru (Don and Peta Rowlands) in Birdsville, the Spinifex people in Tjuntjuntjara, the Martu in Jigalong and the Malgana in Shark Bay. I think they are on to something.

On a final note, I thank my incredible team, partners and generous sponsors of this expedition (2021 and 2023), without whom none of this would have been possible.

In support: Neil and Helen Cocks, Martin and Sandra Bailey, Rick Hunter and Russell Knight

Filmmakers: Mark Game, Gelareh Kiazand, Gavin Rawlings, Morgan Cardiff and Mikey Matthews

Social media: Mike Brailey from Overland Journal Europe assisted with the social media posts during the 2023 journey.

2021 Sponsors and Official Suppliers:

2023 Sponsors and Official Suppliers

Partners 2023:

Leave a Reply