Page 57 – Timbuktu, an ancient city of ‘piety, tolerance, wisdom and justice’

I remember when, growing up, people often used the expression ‘from here to Timbuktu’ to refer to a place that was an inaccessible or an unimaginable distance away. The origin of this notion was born from the fact that, until 1828 when Frenchman René Caillié travelled disguised as an Arab, no European made it out of Timbuktu alive. A number, including Mungo Park, were killed trying. Nowadays people can fly, drive, take a boat, walk, ride a camel…but not too many cycle to the ancient, mystical city of approximately 50,000 inhabitants. As I arrived at the Bouctou Hotel where we had chosen to stay, I was suddenly besieged by a flock of national press, including a well-known Malian media personality with his cameraman. This took me by complete surprise. The embargoes sanctioned by the French government in response to recent kidnappings had rocked the local economy, which relies heavily on tourism. The scene was orchestrated, possibly by government security officials, in an attempt to demonstrate to the public on national and African television that Timbuktu was so safe that ‘even a woman on a bicycle can arrive in one piece, only experiencing friendly, helpful people.’ Of course it was completely true.

We being among only a handful of foreign tourists, like bees to a honey pot, guides, sellers and anyone seeking our business swarmed to compete for our attention. It was difficult to get any peace. Eventually I settled on hiring a guide, Idrissa, who quietened things down somewhat. When Idrissa learned where I was from he said that for the people of Timbuktu, the idea of Australia evoked similar notions as a mystical, faraway land, unreachable to them. Ali Farka Touré expressed a similar sentiment to Idrissa when he said, ‘For some people, when you say “Timbuktu” it is like the end of the world, but that is not true. I am from Timbuktu, and I can tell you that we are right at the heart of the world.’

That afternoon the Timbuktu commune laid on an event which Idrissa explained was ‘an impromptu celebration for peace’, an attempt to promote tourism and raise the spirits of the town. A large crowd milled expectantly in the sandy expanse behind our hotel, Timbuktu’s version of the village green. A band added to the ambience by filling the dusty haze with Saharan rhythms. (Ali Farka Touré’s music would have suited the mood perfectly here.) Traditionally clad Tuareg horsemen showed off their fine riding skills racing by at full gallop while boy jockeys mounted their camels and gathered at the start line. For some reason the camel race never eventuated, but the pomp and colourful processions succeeded in entertaining the masses.

Legend has it that Timbuktu started as a Tuareg camp in the eleventh century. In the Dry season, the inhabitants grazed their animals on burgu grasses (wild millet) around the Niger and in the Rainy season they roamed the desert. Realising that if they camped too close to the river they became sick from mosquitoes and stagnant water, they chose a site a few miles from the banks. When they moved their herds north they left their heavy belongings with a woman named Bouctou. In Tamasheq (Tuareg), bouctou means ’large navel’ and tim is the word for well. Timbuktu, or Tombouctou as it is called in French, therefore refers to the well belonging to Bouctou, lady with the large navel.

Because of its location at the point where the big river meets the desert, Timbuktu evolved as a meeting place for many cultures – a crossroad ‘where camel met canoe.’ African merchants from Djenné traded with Tuareg and Arab traders from the north. Djenné’s architects designed Timbuktu’s first constructions using the same banco, or pounded clay, to which they were accustomed; the Muslim influences came later. Timbuktu’s development gained momentum during the Mali Empire and it was Mansa Musa, the tenth emperor of Mali, who effectively put Timbuktu and his kingdom on the world stage. During his pilgrimage in 1324 to Mecca, accompanied by an entourage including 60,000 men and 12,000 slaves, Musa was so generous with gifts to the cities he passed through, such as Cairo and Medina, that he flooded the market with gold. As a result, the Egyptian currency crashed in value and did not recover for a decade. From that point, the names of Mali and Timbuktu became legendary and were featured on Islamic and European fourteenth-century world maps, whereas previously little had been known beyond the western Sudan.

Returning from his hajj, Musa brought architects from Cairo and Morocco to design the famous Djinguereber Mosque (which was the first attraction Idrissa showed us on his tour). Timbuktu soon became a centre of trade, culture, and Islam. Merchants travelled not only from Nigeria, Egypt and other African kingdoms but also from the Mediterranean cities of Venice, Granada and Genoa. Musa founded universities in Timbuktu as well as in Djenné and Ségou. Islam was spread through the markets and university, making the city a new centre of Islamic scholarship.

Over the following centures Timbuktu’s reputation grew as a Mecca for academia, and Saharan trade routes became more important as ‘ink roads’ for its economy. Our fourteenth-century roaming friend Battuta reported on the piety, tolerance, wisdom and justice of the city’s inhabitants. By AD 1500, Timbuktu’s population of 100,000, twice the size of London at that time, included 25,000 scholars. Arabic professors who took study sabbaticals to Timbuktu were no match for the black academics of Sankoré University, the Oxford or Cambridge of the time, and were sent away to complete bridging courses to bring them up to speed. At a time when Europe was emerging from the Middle Ages, African historians were chronicling the rise and fall of Saharan and Sudanese kings, replete with details of great battles and invasions. Astronomers charted the movement of the stars, physicians provided instructions on nutrition and the therapeutic properties of desert plants, and ethicists debated such issues as polygamy and the smoking of tobacco.

The Songhai Empire, centred 400 kilometres to the east on the River Niger in Gao, succeeded Mali as the next superpower of West Africa. Intellectual and trading status was maintained until the Moroccans invaded and ransacked the city, which started its downward spiral in the late 1500s. The army plundered the wealth, burned the libraries, killed or incarcerated the scholars and pilfered many of the manuscripts. Intellectuals resisted and scholarly activities were driven underground; hundreds of their manuscripts found their way to Fes and Marrakesh in Morocco. Much of the economy dried up as gold was discovered in other parts of the world and European traders, starting with the Portuguese, used ocean routes to connect with Africa rather than crossing the Sahara. During the French colonisation of Mali between 1893 and 1960, many more books and manuscripts ended up in French museums and universities. Only after independence did families again trust that their most prized possessions would not be taken away. West Africa’s historical records slowly began to trickle out from rusting trunks, musty storerooms, dry wells, caves in the desert or from holes dug under the arid sands – wherever they were stashed to protect them from conquerors and colonisers. There are estimated to be up to 700,000 manuscripts held in and around Timbuktu, mostly still kept within the families. The sixty private or public libraries in the city hold about 10 per cent of the manuscripts.

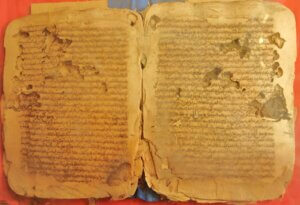

Idrissa arranged for a visit to the Imam as-Sayaouti Library, named after the father of the present Imam of the Djinguereber Mosque. On display was a small collection of manuscripts representative of the 11,000 it contains. Boubacar, a curator and our guide, indicated that the cabinet against the wall, which was crammed full, contained some of the 3000 recent contributions from the community. Over the coming year, the staff’s ‘to do’ list included conserving, digitising, translating and cataloguing each script, although some would have been beyond rescuing. Boubacar explained that people’s private collections were so precious they would sleep, and even choose to die, beside their books. Convincing owners to part with their prized family heirlooms for the purpose of preserving and documenting their content was a challenge and often costly. In villages it might mean building a new mosque or much-needed amenities, or trading a flock of goats in exchange for manuscripts.

The displays were kept out of direct sunlight in a climate-controlled environment. The room was dimly lit by diffused natural light that beamed across the glass cabinets, accentuating the filigree shadows cast by decorations above the front door. The books on show were of varying condition but all were priceless. Boubacar didn’t know the exact age of the oldest volume: it was not new when it was first found in the eleventh century, and then in the fifteenth century the Moroccans stole it and buried it six metres underground. It was rediscovered centuries later and returned to Timbuktu. The curators cannot touch its termite-damaged pages for fear of them atomising into a puff of dust. We also saw an eleventh-century medical text-book about the heart and stomach and a thirteenth-century script bound with goat leather and written in Fulbe (Fulani) – this was unusual because most documents were written in Arabic. We heard from Boubacar about how sixteenth-century Islamic scholars advocated expanding the rights of women, explored methods of conflict resolution and debated how best to incorporate non-Muslims into an Islamic society. A 500-year-old book of Qur’anic law, illustrated with the most skilled, delicate calligraphy, outlined the rights of women, explaining that all Islamic women have the right to spend time to make themselves more beautiful. Detailed astrological diagrams depicted the advanced knowledge of the night sky used to navigate by the stars across the sandy sea.

The oldest book in the Imam as-Sayaouti Library

I could not help but compare and contrast Timbuktu’s fortunes with Oualata’s. As the various kingdoms superseded one another over the centuries, the towns’ scholars sought each other’s sanctuary. If Timbuktu is the ‘navel’ (Bouctou) of the West African intellectual universe then Oualata is merely a satellite in its galaxy. I started to wonder whether there could be some sort of partnership formed with Oualata to share knowledge of conservation and cataloguing of their treasures. Boubacar said that the doors are open but Oualata would need to come to Timbuktu.

He explained that conservation of the scripts is passed down through the generations but that further expertise had been required. The need to locate and preserve the manuscripts was raised four years after independence but Mali being one of the poorest countries in the world, the government has to prioritise its basic needs of keeping the nation fed, watered, healthy and secure. Without the collaborative support from UNESCO, South Africa, the US and Spain in particular, the written record of Africa’s ancient history would gradually be lost.

Stepping outside was like being transported back through the time warp. In the full brightness of day, the sun’s white light bleached the colours of the courtyard. The glare was too much: my pupils recoiled, my eyes watered. Squinting to the point where my lashes joined over the slits in my eyes to filter the blinding rays, I fumbled around for my futuristic cycling sunglasses. Once I’d slipped them on I was back in the present. Completing the contrast from ancient to modern, my mobile phone rang – the Western world calling – someone from London. I made use of the small internet café across the courtyard. With such mod cons, communicating with the outside world from Timbuktu is a little easier these days.

The streets of Timbuktu are certainly not paved with gold as the legend has it. The mud buildings stand as weathering embattlements struggling to resist the encroaching sands, and today they are barely distinguishable from it. We drove the impoverished back lanes to the dune-covered outskirts which serve as the terminus for the camel trains that still bring salt to and from Oualata or Araouane. But we were out of luck: just a handful of camels and goats grazed the sporadic clumps of spiny greenery and the odd nomad went about his business. As we waited out the serene late afternoon in case something appeared on the horizon, Dan and John pulled out their football for a kick around with a couple of lads who had followed us from town. Eventually, the inevitable happened and the ball was spiked by a thorn. The boys pleaded to keep it and, to their delight, got their way. The fact that it was flat wouldn’t have stopped them having hours of fun…